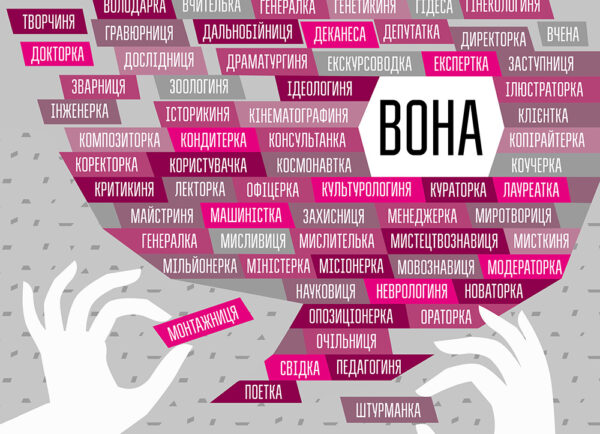

Feminine forms are not a fabrication: why “authoress” and “editress” matter

Ever wonder why no one flinches at “teacher” or “nurse” as feminine terms, but words like “authoress” or “historian (female)” suddenly cause a wave of irritation, especially among men?

It’s not about grammar. It’s about power.

Language is a tool of perception. If you can name someone — you acknowledge their presence. If you can’t name a woman in a role, it likely means you’re still not ready to fully see her there.

Feminine forms aren’t a feminist invention — they’re a reclamation

Feminine forms have existed in Ukrainian language for centuries. In literature, folklore, and everyday speech — words like писарка (female scribe), співачка (singer), купчиха (merchant’s wife), вчителька (teacher) were common and uncontroversial.

Until the Soviet era.

In the 1930s, under the pressure of strict centralization, the USSR launched a massive campaign of linguistic standardization. The idea was simple: mold the language to serve a single ideological system — one where the individual, especially a woman, was reduced to a labor unit, not a social subject.

- Women were framed as “workers”, not agents. They had roles, not voices.

- In professions: “female agronomist”, “female engineer” — but never “agronomka” or “engineeress”.

- In official texts: Stalinist clichés like “heroic worker” or “worthy son of the Motherland” dominated. Women were either silent figures or idealized mothers on posters. That was it.

This wasn’t the language of equality. It was the language of erasure.

The absence of women in the grammatical system was not incidental. It was deliberate — and we’re still dealing with the aftermath.

“Why are you attacking us?” — or why men often react so defensively

Feminine forms tend to provoke resistance — especially from men. That’s not random.

Because it shifts the center.

All your life you’ve been “the director,” “the historian,” “the doctor.” Then one day a woman shows up and says, “I’m the journalist too — but I’m a journalistka, not your shadow.” Suddenly, language doesn’t just serve you. It acknowledges others.

Because it means losing monopoly.

Feminine forms make women visible. And visibility equals power — symbolic, social, professional. And for some, that feels like a loss. Even if they can’t articulate it.

Because it’s uncomfortable.

Men are used to not being challenged by language. Then a new word drops — and suddenly it says, “This world no longer revolves around you.” That’s not aggression. That’s equilibrium.

If the word “authoress” offends you, the problem isn’t the word — it’s your discomfort with shared legitimacy.

And now — facts, not feelings

Feminine forms shape how we think

Studies by UNESCO and the European Parliament have shown that gender-aware language affects career aspirations in young people. If textbooks only refer to “writers”, “scientists”, “inventors” in masculine form, girls are less likely to see themselves in those roles.

Language is not just a mirror — it’s a map

In Sweden, the adoption of the gender-neutral pronoun hen helped reduce gender stereotyping in early childhood groups.

In Ukraine, feminine forms work differently — they reclaim visibility in a language that long pretended women didn’t exist professionally.

Academic language is changing too

More academic journals, university lectures, and official documents are using gendered forms. In 2019, Ukraine’s Ministry of Education issued formal recommendations to use feminine terms in academic and public communication.

Relevant

What does this change actually give us?

- Visibility. A woman is not an exception — she is present, named, and acknowledged.

- New generation thinking. Girls dare to imagine more. Boys learn to share space.

- Linguistic accuracy. Feminine forms don’t limit — they expand.

- Social honesty. If a woman holds a role — the language should reflect it.

And finally

Feminine forms aren’t an attack. They’re not a trend. And they’re definitely not an anti-male crusade.

They’re a recalibration. A habit of speaking in a way that makes everyone visible.

If that still irritates some people — well, maybe that’s the best proof of why they’re necessary.

“If equality makes you uncomfortable — that means it’s working.”

— Written by someone tired of explaining, but still willing to speak