Controlled Arms Exports in 2026 and What They Mean for Ukraine’s Defense Industry

Ukraine’s military-industrial complex is entering 2026 in a condition that only a few years ago seemed impossible. The sector is no longer fighting for survival it is running up against the limits of regulation. After rapidly scaling up the production of drones, long-range systems, and counter-drone solutions, the key question is no longer “can we produce”, but what to do with the surplus without harming the frontline.

That is why arms exports are increasingly defined as one of the main priorities for defense industry representatives in 2026. This is not about shifting focus away from the war toward foreign markets, but about turning excess production capacity into a resource that strengthens Ukraine’s Defense Forces.

Surplus without sacrificing priorities

The core principle insisted on by manufacturers is unequivocal: only verified surplus can be exported, without reducing supplies to the front. This position was clearly articulated by Ihor Fedirko, Executive Director of the Ukrainian Council of Arms Manufacturers:

“This is exclusively about loading surplus production lines without removing the priority of the frontline only confirmed excess will be exported.”

According to an industry survey, 94.4% of companies support opening controlled exports. This figure reflects not political fashion, but production reality. Some lines are already capable of producing more than the state can physically contract within existing budgets and procedures.

How manufacturers see the rules

The main problem today is the absence of a clear and consistent procedure. That is why, according to Fedirko, the focus of 2026 is not on headline-grabbing contracts, but on building a coherent decision-making architecture. The expected logic looks like this:

- verification of the manufacturer and specific product categories;

- interagency assessment;

- confirmation of surplus;

- decision on export approval;

- state safeguards through oversight and post-delivery control.

Separately, a financial safeguard in the form of export duties or fees is being discussed. Its purpose is not fiscal, but strategic. “Surplus is converted into additional domestic contracts, rather than ‘disappearing’ from the war,” Fedirko emphasizes. In this way, exports do not drain resources, but create a closed loop of defense financing.

Why real contracts will not appear immediately

Despite manufacturers’ readiness and existing contacts with partners, even market players themselves do not expect a rapid start to exports. The reasons are pragmatic and not limited to Ukraine alone. The main constraints include:

- the domestic permitting mechanism;

- testing and certification cycles on the partners’ side;

- complex procurement procedures of foreign buyers.

That is why the first full-fledged export contracts look realistic in the second half of 2026. Until then, companies will be preparing products for compliance, conducting demonstrations, finalizing documentation, service and training packages, spare parts logistics, and repair support.

Drones as the base and long-range capability as the trend

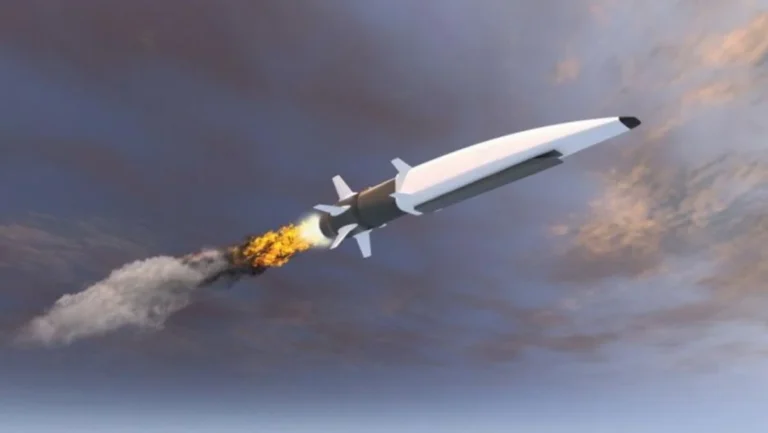

In 2025, Ukraine’s defense industry produced three times more unmanned aerial vehicles than the year before. The state made drones the backbone of warfare, while long-range capability became a strategic priority.

According to Fedirko:

- drones of various types have become the foundation of the defense industry;

- FPV drones and multicopters cover the daily tactical needs of units;

- deep strike and mid-strike have moved from experimentation to systemic practice;

- counter-drone systems are growing into a separate critical category.

He stresses:

“The third major category that grew steadily throughout the year is counter-drone systems: interceptors, electronic warfare, sensors, communications, and everything that increases the effectiveness of site protection and reduces the use of expensive air defense missiles.”

Post List

Expectations for the coming year are restrained but clear. The trend will not change, but requirements will become stricter:

- protection of communication channels;

- rapid upgrade cycles against electronic warfare;

- new frequency profiles;

- integration with reconnaissance and targeting systems.

Еxports cease to be a symbol of “entering markets”. They become an indicator of whether the state is capable of building a complex control system without weakening the frontline.

Controlled arms exports in 2026 are not about politics or profits. They are a test of institutional maturity. Ukraine’s defense industry has already proven it can scale production quickly and adapt to the warfare of the future. Now the question is different: can the state create rules that allow this potential to work for defense, rather than simply accumulating unused capacity on factory floors. If such rules emerge, surplus will become a resource. If not, it will remain lost time in a war where every month matters.