New Research: Mitochondrial DNA in Egg Cells Remains Stable

In August 2025, an international team of scientists from MIT, Harvard, Leiden University, and other institutions published a landmark study in Science Advances: “Allele frequency selection and no age-related increase in human oocyte mitochondrial mutations” (Arbeithuber B. et al., 2025).

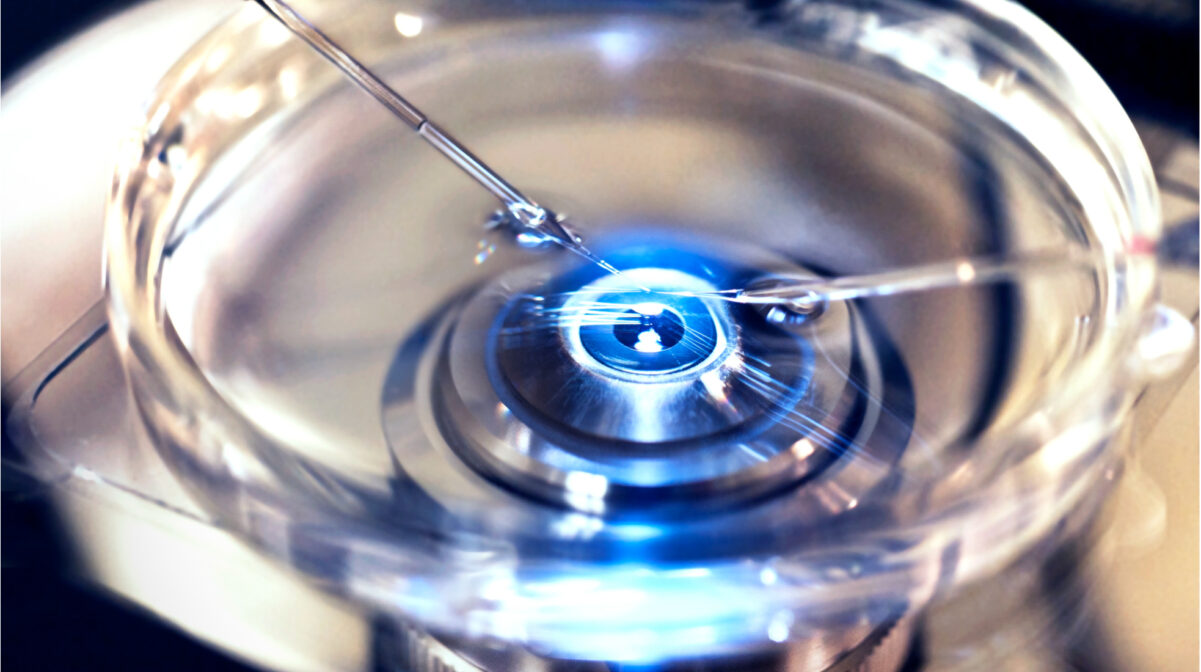

The researchers analyzed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the egg cells of 22 women aged 20 to 42, using ultra-precise duplex sequencing technology. For comparison, they also examined blood and saliva samples from the same women.

The results were unexpected even for the scientific community:

“We did not detect a statistically significant increase in the number of mitochondrial mutations in oocytes with female age, while such dependence is obvious in blood and saliva,” the original article states.

The mutation rate in egg cells was 17-24 times lower than in blood or saliva, regardless of the woman’s age. Moreover, “harmful” mutations were less common in coding (important) regions of mtDNA, indicating an effective natural defense purifying selection, or natural “cleansing” of genetic material even during oogenesis.

“The mitochondrial DNA of human oocytes possesses special protective mechanisms against the accumulation of age-related mutations,” comments lead author Barbara Arbeithuber.

Why Female Egg Cells Don’t “Age” the Way Old Medicine Imagined

In women, all egg cells are formed before birth and then remain “frozen” until ovulation. They don’t undergo dozens of division cycles like body cells or male sperm, so they don’t accumulate random mutations with age.

This means: egg cells retain the “quality” of their mitochondrial DNA even if a woman becomes a mother at 35, 40, or even 42.

Men and the Risk of Age-Related Mutations: How the “Biological Clock” Really Works

Unlike women, men’s sperm are produced continuously throughout life, with each new wave of cells undergoing dozens of division cycles. With each cycle, new random mutations accumulate.

A number of studies (Nature Reviews Genetics, 2019; Human Reproduction Update, 2022; Cell, 2021) have long shown:

- The older the father, the higher the risk of “de novo” mutations in children.

- Age-related mutations in sperm are linked to increased risks of autism, schizophrenia, achondroplasia, Down syndrome, and other genetic disorders.

- Lifestyle factors lack of exercise, chronic stress, poor nutrition, smoking, obesity further increase the risk of DNA damage in sperm.

“The mutational load accumulating in male germ cells with age is significantly greater than in female oocytes,” emphasize the authors of a meta-analysis in Human Reproduction Update.

Post List

Why This Challenges Soviet-Era Myths About “Women’s Fault”

In Soviet and post-Soviet societies, responsibility for the “biological clock” was often placed solely on women. Problems with carrying a pregnancy, birth defects, even unsuccessful IVF attempts were traditionally blamed on “old eggs.” New data convincingly show: in most cases, the main risk of new mutations depends on the age and lifestyle of the father.

“The paradox is that oocytes, which do not renew and are preserved for decades, show genetic stability. Meanwhile, sperm, which are constantly renewed, accumulate mutations with age,” states a Cell (2021) review.

The latest genetic research confirms: female egg cells have unique protection against mitochondrial aging, and the risk of age-related mutations in offspring is primarily determined by the father’s age, not the mother’s.

This means:

- Women have the right to make their own reproductive choices without stigma from the “biological clock.”

- Men who plan to become fathers at an older age need to take responsibility for their health.

- Medical education and reproductive programs must shift their emphasis in explaining age-related risks.

“Most of what we thought we knew about egg cell aging does not correspond to reality. The key problem is in the male genome,” comment the Science Advances study authors.

Modern science is restoring reproductive justice and changing old perceptions of the “biological clock” it doesn’t just tick for women, but much more often for men. And the best time to talk about it is now.