The “Parisian Girl” Myth: how marketing and TV turned style into a tool for controlling women

The image of a “French girl” with minimal makeup, a tousled fringe and a woven basket has become a productsold together with a lipstick, a perfume and “proper” eating habits. It is not just aesthetics, but a system of expectationsabout a woman’s body, age, class and behaviour.

In the popular imagination, Parisian aesthetics looks like this: white T-shirts, jeans, a plain shirt, minimalist jewellery, light makeup. The historical reference is obvious Jane Birkin and her pared-back silhouettes. It really is “classic” that works across decades: the rise of jeans or the palette may change, but the silhouette and the way of combining pieces stays intelligible and accessible.

Here is the first trap. Minimalism on Instagram is framed as “got dressed in 10 minutes and went for croissants”. But this “ease” is not free: it requires quality basics, time for grooming, cultural capital, and a particular city as a backdrop. In the end the “effort is invisible”, yet it exists it is women’s labor that has been hidden.

Commercialising the myth: how a lifestyle is sold

Brands quickly turned the myth into a marketing conveyor belt. The logic is simple: buy the eyeshadow/lipstick/fragrance and receive the feeling of being a Frenchwoman.

“they sell not just products; they sell that very lifestyle.”

As a result, minimalism becomes expensive: “you can buy a Birkin bag that looks simple, but costs like half an apartment.” Even the “basic” foundation, lipstick or fragrance is never “finally right” in this logic tomorrow a new product drops and you again chase the trend. It is an endless race after a deferred ideal.

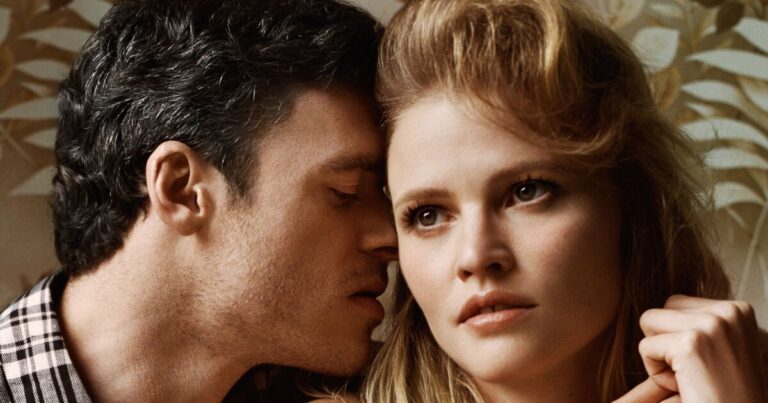

“Emily in Paris”: a shop window instead of a city

The clearest example of fetishisation is the series “Emily in Paris”. “a beautiful shop window” where only a luxury lifestyle exists, and where “supercilious, angry French people” endlessly smoke, drink wine and revolve around sex, food and perfume.

The irritation is not only about shallowness, but about national stereotypes, including the episode with a stereotyped Ukrainian woman. A telling linguistic detail: “why is everyone speaking English?” people ask in French discussions. Real Paris sounds French, not just like a global platform’s default.

From a feminist lens the window is polished for the male, advertising and tourist gazes, where a woman is mainly a bearer of style and a character in a love triangle. Social reality queues for croissants on weekends, rubbish, protests, migrants, youth, different bodies and ages falls out of frame. Thus a city-as-attraction is born, where “living” gets replaced by “looking”.

“French diets” as an extension of control over the body

The marketing of style naturally slides into the marketing of corporeality. The archetype of the “Parisian girl” embeds the idea of disciplined slimness from the “leek soup” to a book promising that “French women don’t get fat”.

“there’s nothing healthy about this soup: a bunch of leeks, 2 litres of water, two days and fewer kilos.” French discussions often describe this as a culture of shame: outwardly “softer”, but with constant criticism of extra weight, especially toward those who fall outside “slender” norms.

From a feminist perspective it’s a classic mechanism: control over the body is packaged as self-discipline and ‘care’, and in practice becomes a form of internal censorship. “Effortless” turns into invisible work daily calorie counting, comparing oneself to the shop window, guilt.

Real voices from the city: what doesn’t fit the window

A Paris-based creator like Lucille brings us back to everyday truth: weekend queues “when you just want a croissant”, diverse faces, non-perfect hair, no “mandatory” basket with lavender. Paris here is a city of protests and diversity, not just a backdrop for selfies.

That matters, because diversity is the key argument against a one-dimensional ideal. If we see “Frenchness” only as “thin, younger, white, wealthy and forever neat”, we erase most real women.

Post List

Why the stereotype survives

- Marketing: the myth is easy to monetise; it’s packaged into a lipstick, fragrance, trench.

- Algorithms: platforms boost the glossy and repeatable it “sticks” better.

- Simplicity of the image: “white tee + jeans” is an easy code promising quick results.

- Class and access: “ease” rests on money and time, but that is hidden.

- Culture of shame: “ease” is fused with “slimness”, and then with a woman’s “value”.

What media and audiences can do

- Name the mechanisms: if a lifestyle is being sold, say so; it’s advertising, not “Parisian in a bottle”.

- Show body and age diversity: real Parisian women are varied. There isn’t one norm.

- Differentiate care from control: self-care is fine; guilt is not.

- Ask class questions: how much does “ease” cost and who can access it.

- Learn from local voices: look not only at the shop window, but at the city’s everyday life.

Quotations worth preserving

- “it’s just a beautiful shop window… where you’re shown a luxury lifestyle that doesn’t exist in reality.”

- “they sell not just products; they sell that very lifestyle.”

- “there’s nothing healthy about this soup… you drink it for two days to drop weight.”

Why this stereotype is so resilient

Because it is simple, profitable and convenient. It promises identity without history, “ease without work”, “slimness without consequences”. From a feminist perspective this isn’t only about things; it’s about power over women’s bodies and time.

Real Paris is a city of different women with different incomes, habits and bodies. Real “ease” is not a new lipstick or leek soup, but the right to be yourself with or without curls, in a trench or a hoodie, with or without a croissant, without counting calories.

When we see how the shop window is assembled, we reclaim our subjectivity. And we change the question: instead of “how to become a Parisian girl”, we ask who profits from this, what it hides, and what we’re willing to pay for it.